Press & Brochures

Text of Richard Klein's essay:

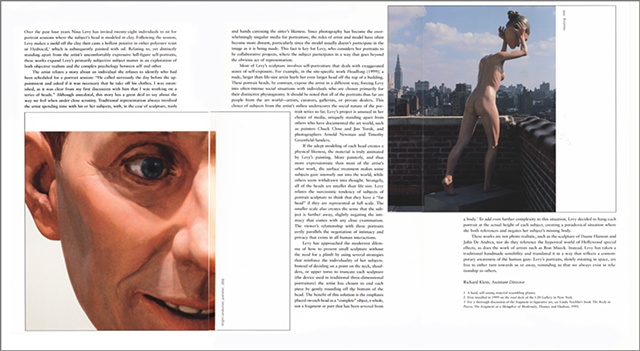

Over the past four years, Nina Levy has invited twenty-eight individuals to sit for portrait sessions where the subject's head is modeled in clay. Following the session, Levy makes a mold off the clay and then cast a hollow positive in either polyester resin or Hydrocal, which is subsequently painted with oil. Relating to, yet distinctly standing apart from the artist's uncomfortably expressive full-figure self-portraits, these works expand Levy's primarily subjective subject matter in an exploration of both objective realism and the complex psychology between self and other.

The artist relates a story about an individual she refuses to identify who had been scheduled for a portrait session: "He called nervously the day before the appointment and asked if it was necessary that he take off his clothes. I was astonished, as it was clear from my first discussion with him that I was working on a series of heads." Although anecdotal, this story has a great deal to say about the way we feel when under close scrutiny. Traditional representation always involved the artist spending time with his or her subjects, with, in the case of sculpture, tools and hands caressing the sitter's likeness. Since photography has become the overwhelmingly singular media for portraiture, the roles of artist and model have often become more distant, particularly since the model usually doesn't participate in the image as it is being made. The fact is key for Levy, who considers her portraits to be collaborative projects, where the subject participates in a way that goes beyond the obvious act of representation.

Most of Levy's sculpture involves self-portraiture that deals with exaggerated states of self-exposure. For example, in the site-specific work Headlong (1990), a nude, larger that life-sized artist hurls her even larger head off the top of a building. These portrait heads, by contrast, expose the artist in a different way, forcing Levy into often-intense social situations with individuals who are chosen primarily for their distinctive physiognomy. It should be noted that all of the portraits thus far are people from the art world- artists, curators, gallerists, or private dealers. This choice of subjects from the artist's milieu underscores the social nature of the portrait series so far. Levy's project is unusual in her choice of media, uniquely standing apart from others who have documented the art world, such as painters Chuck Close and Jim Torok, and photographers Arnold Newman and Timothy Greenfield-Sanders.

If the adept modeling of each head creates a physical likeness, the material is truly animated by Levy's painting. More painterly, and thus more expressionistic than most of the artist's other work, the surface treatment makes some subjects gaze intensely out into the world, while others seem withdrawn into thought. Strangely, all of the heads are smaller than life size. Levy relates the narcissistic tendency of subjects of portrait sculpture to think that they have a "fat head" if they are represented at full scale. The smaller scale also creates the sense that the subject is further away, slightly negating the intimacy that comes with any close examination. The viewer's relationship with these portraits eerily parallels the negotiation of intimacy and privacy that exists in all human interactions.

Levy has approached the modernist dilemma of how to present small sculpture without the need for a plinth by using several strategies that reinforce the individuality of her subjects. Instead of deciding on a point on the neck, shoulders, or upper torso to truncate each sculpture (the device used in traditional three-dimensional portraiture) the artist has chosen to end each piece by gently rounding off the bottom of the head. The benefit of this solution is the emphasis placed on each head as a "complete" object, whole, not a fragment or part that has been severed from a body. To add even further complexity to this situation, Levy decided to hang each portrait at the actual height of each subject, creating a paradoxical situation where she both references and negates her subject's missing body.

These works are not photo realistic, such as the sculpture of Duane Hanson and John De Andrea, nor do they reference the hyperreal world of Hollywood special effects, as does the work of artists such as Ron Mueck. Instead, Levy has taken a traditional handmade sensibility and translated it in a way that reflects a contemporary awareness of the human gaze. Levy's portraits, slowly rotating in space, are free to either turn towards us or away, reminding us that we always exist in relationship to others.

COPYRIGHT ALDRICH MUSEUM AND RICHARD KLEIN 2003