Press & Brochures

Text of the interview:

Leah Oates: Your sculpture is very life-like but has this very odd twist in the end. It is both familiar and jarring for a viewer which gives it a depth that makes one want to slow down and try to figure out what is going on. Can you speak about this contrast as well as the narrative in your work?

Nina Levy: I am always interested in making ambivalent objects–things that can be both pleasing and ingratiating and unsettling or offensive at the same time. Ambivalence is even more of an issue for me as I am working with subject matter that has a strong potential to be cute or insipid. My work process starts with a twist, distortion or fragmentation that is usually formal in origin. I try to let a simple physical relationship generate the narrative and then I attempt to leave it as open to interpretation as possible.

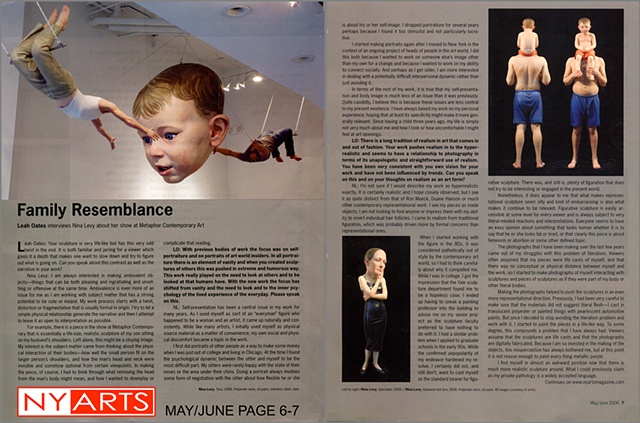

For example, there is a piece in the show at Metaphor Contemporary that is essentially a life-size, realistic sculpture of my son sitting on my husband’s shoulders. Left alone, this might be a cloying image. My interest in the subject matter came from thinking about the physical interaction of their bodies–how well the small person fit on the larger person’s shoulders, and how the man’s head and neck were invisible and somehow optional from certain viewpoints. In making the piece, of course, I had to think through what removing the head from the man’s body might mean, and how I wanted to downplay or complicate that reading.

LO: With previous bodies of work the focus was on self-portraiture and on portraits of art world insiders. In all portraiture there is an element of vanity and when you created sculptures of others this was pushed in extreme and humorous way. This work really played on the need to look at others and to be looked at that humans have. With the new work the focus has shifted from vanity and the need to look and to the inner psychology of the lived experience of the everyday. Please speak on this.

NL: Self-presentation has been a central issue in my work for many years. As I used myself as sort of an "everyman" figure who happened to be a woman and an artist, it came up naturally and consistently. While like many artists, I initially used myself as physical source material as a matter of convenience; my own social and physical discomfort became a topic in the work.

I first did portraits of other people as a way to make some money when I was just out of college and living in Chicago. At the time I found the psychological dynamic between the sitter and myself to be the most difficult part. My sitters were rarely happy with the state of their noses or the area under their chins. Doing a portrait always involves some form of negotiation with the sitter about how flexible he or she is about his or her self-image. I dropped portraiture for several years perhaps because I found it too stressful and not particularly lucrative.

I started making portraits again after I moved to New York in the context of an ongoing project of heads of people in the art world. I did this both because I wanted to work on someone else’s image other than my own for a change and because I wanted to work on my ability to connect socially. And perhaps as I get older, I am more interested in dealing with a potentially difficult interpersonal dynamic rather than just avoiding it.

In terms of the rest of my work, it is true that my self-presentation and body image is much less of an issue than it was previously. Quite candidly, I believe this is because these issues are less central to my present existence. I have always based my work on my personal experience, hoping that at least its specificity might make it more generally relevant. Since having a child three years ago, my life is simply not very much about me and how I look or how uncomfortable I might feel at art openings.

LO: There is a long tradition of realism in art that comes in and out of fashion. Your work pushes realism in to the hyperrealistic and seems to have a relationship to photography in terms of its unapologetic and straightforward use of realism. You have been very consistent with you own vision for your work and have not been influenced by trends. Can you speak on this and on your thoughts on realism as an art form?

NL: I’m not sure if I would describe my work as hyperrealistic exactly. It is certainly realistic and I hope closely observed, but I see it as quite distinct from that of Ron Mueck, Duane Hanson or much other contemporary representational work. I see my pieces as made objects; I am not looking to fool anyone or impress them with my ability to insert individual hair follicles. I came to realism from traditional figuration, which was probably driven more by formal concerns than representational ones.

When I started working with the figure in the 80s, it was considered pathetically out of style by the contemporary art world, so I had to think carefully about why it compelled me. While I was in college, I got the impression that the Yale sculpture department found me to be a hopeless case. I ended up having to sneak a painting professor into the building to advise me on my senior project as the sculpture faculty preferred to have nothing to do with it. I had a similar problem when I applied to graduate schools in the early 90s. While the confirmed unpopularity of my endeavor hardened my resolve, I certainly did not, and still don’t, want to cast myself as the standard bearer for figurative sculpture. There was, and still is, plenty of figuration that does not try to be interesting or engaged in the present world.

Nonetheless, it does appear to me that what makes representational sculpture seem silly and kind of embarrassing is also what makes it continue to be relevant. Figurative sculpture is easily accessible at some level for every viewer and is always subject to very literal-minded reactions and interpretations. Everyone seems to have an easy opinion about something that looks human whether it is to say that he or she looks fat or tired, or that clearly this piece is about feminism or abortion or some other defined topic.

The photographs that I have been making over the last few years came out of my struggles with this problem of literalism. Viewers often assumed that my pieces were life casts of myself, and that there was no conceptual or physical distance between myself and the work, so I started to make photographs of myself interacting with sculptures and pieces of sculptures as if they were part of my body or other literal bodies.

Making the photographs helped to push the sculptures in an even more representational direction. Previously, I had been very careful to make sure that the materials did not suggest literal flesh–I cast in translucent polyester or painted things with pearlescent automotive paints. But once I decided to stop avoiding the literalism problem and work with it, I started to paint the pieces in a life-like way. To some degree, this compounds a problem that I have always had: Viewers assume that the sculptures are life casts and that the photographs are digitally fabricated. Because I am so invested in the making of the objects, this misperception has always bothered me, but at this point it is not reason enough to paint every thing metallic purple.

I find myself in almost an awkward position now that there is much more realistic sculpture around. What I could previously claim as my private pathology is a widely accepted language. It is more confusing to be perceived as part of a trend than to be outside it. When "The Body" became popular in the critical discourse of art magazines in the early 90s, I had some difficulty establishing how my work related to it. In every conversation about my work, I had to explain where I stood in relation to Kiki Smith. Ron Mueck’s name is more likely to come up now.

LO: You recently had a son as did I. How do you think this has changed your work if at all? I’m asking mainly as it’s not talked about much in the art world. Many artists are mothers and it seems to be less of a taboo subject than it used to be, but it is not quite there yet I think. What are your thoughts on being an artist and a mother?

NL: Needless to say, having a child is not a savvy career move in almost any profession. In its acceptance of idiosyncratic and individualistic behavior, the art world does seem more forgiving than some other areas, but I suspect that is not the whole story. It is hard enough to be taken seriously in a profession, which is pretty "unprofessional," much of the time. And difficult to combat the unspoken assumption that once one becomes someone’s mother and primary caretaker, one cannot possibly continue to make serious work. While I find this assumption distressing, let me be honest, it is brutally difficult to make work while dealing with the bottomless well of need that has taken up residence in my house. I am still working, but the cost is extremely high.

Beyond the obliterating sleep deprivation, there is no doubt that the existence of my son has had a profound effect on what I do in the studio. In a passive-aggressive fashion, I took what was most problematic about the situation and made it the subject of the work. I felt that it would be best for me professionally to continue as if there had been no change in the circumstances of my life, but instead I find myself making work about just how overwhelming it is to be a parent. This embarrasses me in just the way that making figurative sculpture has always embarrassed me. I felt particularly pathetic making a giant baby sculpture when my son was only a few months old. I had a compulsion to tell anyone who passed through my studio that a museum had asked me to make the piece and that I was not just working through some sort of ridiculous maternal obsession.

LO: What influences you as an artist and how did you become an artist? Some artists are from backgrounds where there is art and others are not. For some it is art theory that is inspiring and for other is music. What inspires you to make art?

NL: My parents both went to art school in the 60s, and then thought better of it and started a very successful design business. I had plenty of exposure to visual culture from a very early age, but always thought art to be an unwise career choice. Making things was always a primary way of being, and I still feel almost as if I would not exist were I not making something. My influences and source material have been theoretical in the past, but lately it is probably more pop cultural detritus than critical theory that creeps into my work.

LO: What projects do you have coming up and what will you be working on in the studio next?

NL: I have two projects in the immediate future. I am making a site-specific piece for the opening of the new building for the Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago in April. The opening exhibition is called "Takeover" and all of the installations are supposed to respond to, comment on or disrupt the building. My piece Drop is sited in a stairwell where the landing on the second floor can be seen from the first floor. There are two components to the piece. A small child standing on a stool leans over the railing looking down at the floor beneath him. Directly underneath him on the first floor is an oversized woman’s head, which has been squashed more or less flat, perhaps by impact. The head and child are roughly based on my son and myself although neither is strictly a likeness or a portrait.

I am also working on a show of portraits for the reopening of the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. this summer. The museum is including five small shows of work by contemporary artists. I have done portraits of the other four contemporary artists and will also show a life-size standing figure who is wearing an oversize head.

COPYRIGHT 2006 NY Arts Magazine